The ANPR data leak that shook Britain: new discoveries and lessons learned.

The recent ANPR data leak raised questions regarding privacy versus data security with public surveillance systems. How do private and public organizations maintain transparency while protecting personal data?

On April 28, 2020, The Register reported the massive Automatic Number-Plate Recognition (ANPR) system used by the Sheffield government authorities was leaking some 8.6 million driver records. An online ANPR dashboard responsible for managing the cameras, tracking license plate numbers and viewing vehicle images was left exposed on the internet, without any password or security in place. This meant anybody on the internet could have accessed the dashboard via their web browser and peeked into a vehicle’s journey or possibly corrupted records and overridden camera system settings.

ANPR is a complex system of interconnected roadway cameras that automatically capture vehicles’ license plates and run the numbers through government databases for potential matches. This is useful for the police in enforcing speeding penalties and identifying known adversaries in deterring crime and terrorism.

The ANPR system also generates significant revenue for the government. “ANPR is a valuable system – generating fines of upwards of £200 million and being structurally significantly more efficient than having roaming speeding police,” says Andy Barratt, managing principal of Coalfire. “The system is either loved or loathed depending on the horsepower you have at your disposal.”

The Council and South Yorkshire Police have suggested there were no victims of the data leak, but experts aren’t so sure. “First, I don’t know that we can be confident in their ability to identify whether anyone has improperly accessed or exfiltrated this data, particularly given the egregious situation which resulted in this data breach,” says Dave Stapleton, CISO of CyberGRX. “Second, if the data was exfiltrated and intended to be sold on the dark web or used for social engineering purposes, we may not know whether anyone has or will suffer harm for some time.”

“As forensic investigators, we have often come across data breaches where the reason there were no signs is because there [were] no systems monitoring for signs,” says Barratt. “No evidence of compromise is not the same as evidence of no compromise.”

Regardless of whether private data fell into the wrong hands, the ANPR leak underscores the risks of exposing data that is mandated to stay private while complying with regulatory requirements to make other data publicly accessible. That task becomes more complicated when the data is gathered by a surveillance system like the ANPR.

Public IoT data comes with privacy, security risks

In many places around the world, including the UK, traffic cams are publicly accessible. UK open governance laws and open data initiatives ensure civilians have a legal pathway to access government information that would otherwise have been restricted, allowing for greater transparency and “policing by consent.”

Cameras used for road surveillance, law enforcement and insight into traffic accidents are no exception. Like IoT devices such as your home router, smartphone or smart watch, traffic cameras are internet-connected. They also can collect data for multiple purposes.

For example, the ANPR system need not always use specially commissioned yellow-colored cameras for the task. In many cases, the same CCTV cams that provide live information on traffic congestion can also be used for basic speed enforcement tasks.

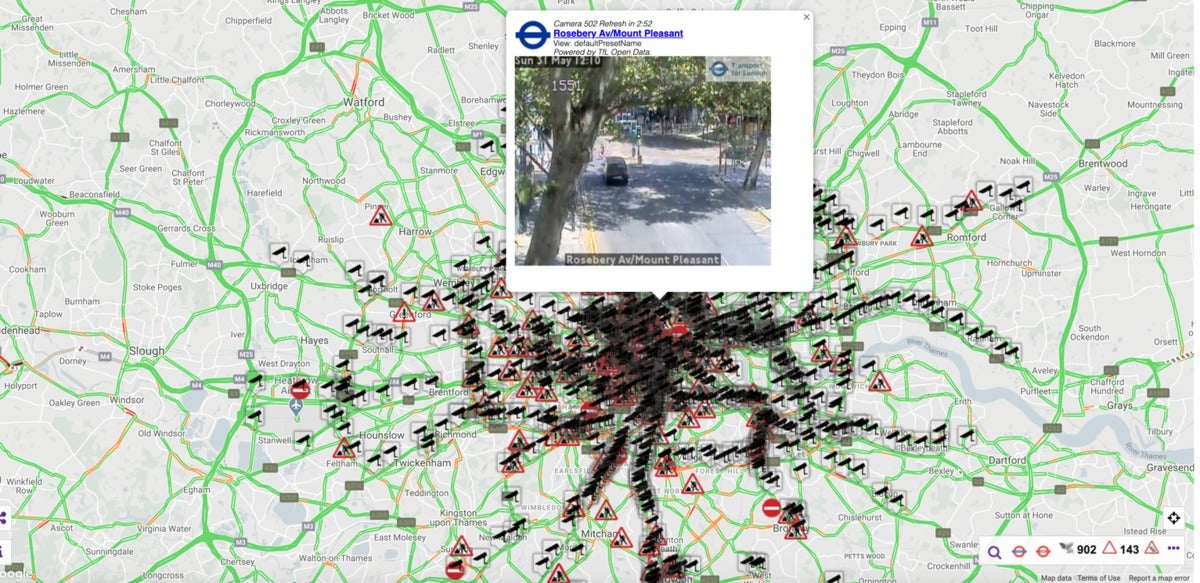

In my independent research I discovered, located not far from a “Police ANPR in use” sign in Vauxhall, London are what appear to be CCTV cameras (on the two ends of the road) with “speed camera” symbols. The live, lower-quality feed from these is recorded and broadcasted every 5 minutes and remains freely accessible to the public via Transport for London (TfL).

This is true for at least 877 TfL “jamcams” offering well over 1,000 live streams in London alone as evident from these publicly accessible AWS buckets. Any technologically savvy user can tap into them. Likewise, the government-owned company, Highways England, is responsible for providing similar visibility into the UK roadway network via its TrafficEngland website. While the IPv4 addresses for these cameras are not advertised, their content is openly disseminated to civilians.

IoT devices, public IPs and port scans

Naturally, this opens up a paradoxical challenge for IT professionals and business policymakers to solve when making decisions concerning data security. IoT search engines like Shodan and Censys.io constantly sweep the web for public IP addresses and open ports commonly used by IP-cams and make them available for anyone to view. Many devices are either secured with easily guessable default username-password combinations or have no password protection.

If you have ever typed a local address (http://192.168.0.1/) into your web browser to access your home WiFi router’s or printer’s admin interface, IP cams work in a similar fashion. If your router, IP camera or smart printer, for example, has remote-administration enabled and no password in place, a malicious actor could find your device on Shodan and potentially compromise your device and enterprise network.

Configuring remote IoT devices and the possible risks

A challenge with securing IoT devices such as mass surveillance cameras is their sheer volume. They must be individually configured and hardened while ensuring open access to them. This makes the task of the sysadmins and security professionals cumbersome. You can’t easily provide open access to tens of thousands of camera systems while simultaneously restricting access to them in the name of security.

Also, because search engines are constantly indexing internet-facing servers and IoT devices, increased risks and a larger attack surface come with their exposure. Securing every individual device, however, adds technological overhead and complexity for IT professionals, and may even impact a system’s speed and performance. It’s a constant battle between security and practical usability.

In addition to the vehicle movements being captured, these cameras are also capturing faces. While “reasonable expectation of privacy” legal doctrines around the world exempt public surveillance cameras from being categorized as “invasive,” it’s a different story when the same devices are generating data on millions of vehicles and tracking their movements. Although the live feeds from these cameras need not be restricted, personally identifiable data like license plate numbers and an entire ANPR administration dashboard, meant for the eyes of law enforcement only, very much need protection. Disregarding this requirement gives criminals an opportunity to evade such public safety measures.

The Sheffield data leak might have happened because the dashboard was on the same IP subnet as public-facing cameras, leaving the dashboard and cameras accessible remotely. “As it was described, the system was ‘breached’ simply by accessing it over the internet,” says Mike Weber, VP of Coalfire Labs. “To me, it’s so blatantly insecure that it sounds like this was an intended feature! It’s getting increasingly more complex to allow access to systems remotely, and more so, without a password. Surely, the engineers that configured this had to take deliberate steps to allow this to occur. But I would also assume that global, unauthenticated access was not the intention of the engineers that architected this system.”

At this writing, the city of Sheffield traffic cameras that should remain accessible to the public are no longer showing up for viewing, perhaps given recent events. The Sheffield City Council did not respond to a request for comment.

Privacy, data security and public trust in organizations

Whether it’s the government or your business organization, basic data security measures need to be implemented and verified at all times to keep confidential information locked away from prying eyes. It also ensures users that your organization can be fully entrusted with handling sensitive data.

The UK’s Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 imposed tighter regulations and established clear procedures on how information pertaining to surveillance systems including CCTV cameras and ANPR systems should be handled. While open data access to CCTV cameras ensures greater transparency, the same functionality can be misused to invade someone’s privacy. For example, a recent report reveals how the extensive camera network and maps could be used to track journeys of alleged lockdown offenders, including British politician Dominic Cummings.

If the information being collected and stored by the government or their contractor companies falls into the wrong hands, it can be detrimental to a user’s privacy. “Breaches like this worry me, especially as numerous governments are currently developing COVID-19 contact tracking apps that could include user identifiable information, which if not secured properly, could be misused by bad actors,” says Chris Hauk, consumer privacy champion with Pixel Privacy.

The points made by Hauk are relevant and come at a time when data breaches are on constant rise. The open-source NHS tracking app had security and privacy bugs discovered right before its release. Moreover, last week a UK-based healthcare company was inadvertently leaking doctor-patient video consultations, something regarded highly confidential, via their smartphone app.

Are these surveillance systems any riskier than what users are already, voluntarily telling popular apps, services and IoT devices about themselves? “Citizens across the world are subjected to this type of surveillance every day, from your smartwatch activity, Ring doorbell, bank or airport cameras, and more, so the risk to consumers, at least on the surface, is no higher than other apps,” said Daniel Smith, head of security research at Radware.

“Think of it this way: Unlike your credit card that is kept hidden in your wallet, your license plate number is visible all day long to other drivers or those on the street, and can be easily tied to you without extensive capabilities or hardware. A malicious actor may be able to find that one person drove to a specific location through the leaked ANPR data, but this would likely be already known from what you’re doing online or social media posts you’re mentioned in.” Smith’s comments place a greater responsibility on both the government and private organizations with regards to securing their users’ private data.

“Often there are unintended consequences to our actions,” says Mark Sangster, vice president and industry security strategist at eSentire. He cited the example of the fitness tracking app Strava that “was collecting exercise metrics and telemetry from connected devices (phones, watches, bands) to improve health and maximize the output of exercise regimes. And this information was shared across social media services.” But because Strava was used by military personnel, the company had unintentionally created maps of secret military bases.

Similarly, if not properly secured, data collected by connected surveillance systems can be abused by state-sponsored actors and pose a threat to national security, mentioned Sangster. For example, to “determine high traffic or stall points to ensure maximum harm is inflicted in an attack, [or] track back number-plates to owners to identify high-net-worth individuals or public figures to kidnap or attack them, or corporate vehicles carrying high-value cargo (expensive merchandise, armored car bank transfers, alcohol or tobacco, etc.)” among others.

Incidents like this one have compelled experts from multiple sectors and industries to think outside of the box. There’s the challenge of ensuring greater privacy and data security to users, while still offering “open access” to systems for transparency’s sake, as demanded by legislation. Yet, the public continues to expect law enforcement authorities and contractors to excel at their jobs of catching criminals via surveillance data, leaving no easy solution for the government.

There will always be a tradeoff for IT and security professionals, policymakers and users to accept: There are security risks from exposing connected devices should the data they collect fall into wrong hands. Heavily restricting access via firewalls may have a negative impact on their performance and user experience. A balance needs to be achieved here for delivering an optimal solution.

This article authored by Ax Sharma originally appeared on CSO Online.